Graham-Cassidy-Heller-Johnson Bill Would Reduce Federal Funding to States by $215B

Summary

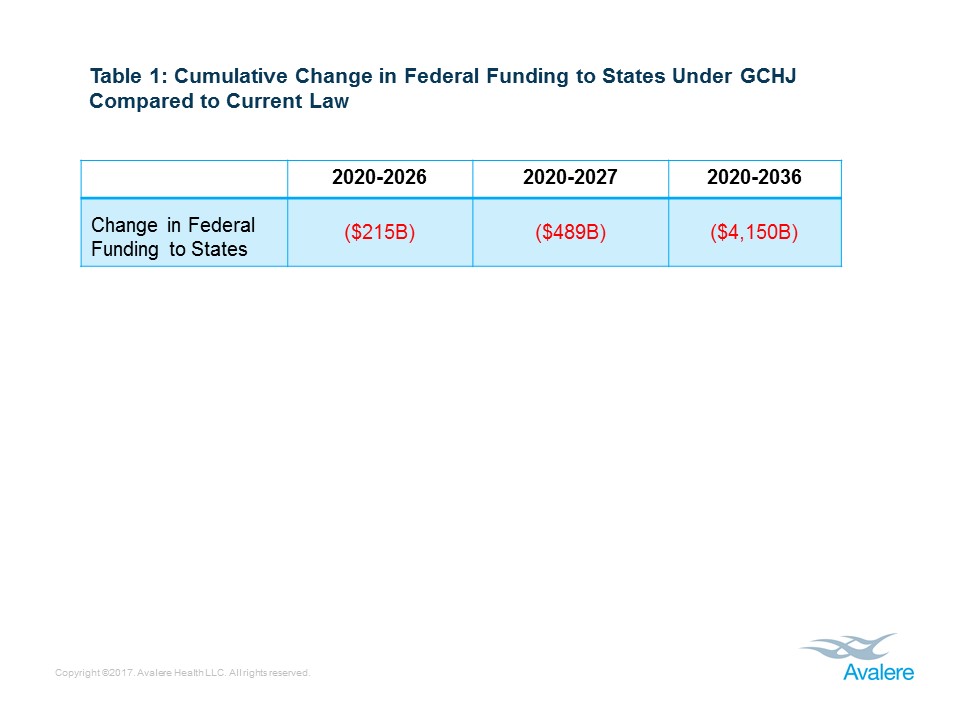

New analysis from Avalere finds that the Graham-Cassidy-Heller-Johnson (GCHJ) bill to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would lead to a reduction in federal funding to states by $215B through 2026 and more than $4T over a 20-year period (Table 1).The proposed legislation would repeal the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, premium tax credits, cost sharing reduction (CSR) payments, individual and employer mandates, and the Basic Health Program (BHP). Instead, the bill would provide states with block grants to fund health insurance coverage in their state. The bill would also change the financing structure for the traditional Medicaid population from an open-ended approach to a fixed per capita cap or block grant approach.

“The Graham-Cassidy bill would significantly reduce funding to states over the long term, particularly for states that have already expanded Medicaid,” said Caroline Pearson, senior vice president at Avalere. “States would have broad flexibility to shape their markets but would have less funding to subsidize coverage for low- and middle-income individuals.”

Avalere’s analysis projects the impact of the bill compared to current law and details the expected cumulative changes in federal funding for each state through 2026, 2027, and 2036.

Funding cuts vary dramatically by state, including cuts for 34 states and DC

Years 2020–2026: By 2026, the bill—compared to current law—would lead to 34 states and DC experiencing funding cuts; 7 states seeing funding reductions above $10B; and 16 states seeing an increase in funding (Figure 1).

“The largest impact of the proposed bill would be the reallocation of federal dollars between states,” said Elizabeth Carpenter, senior vice president at Avalere Health. “Medicaid expansion states and states that have enrolled a high number of people in insurance affordability programs would be most adversely impacted.”

The bill then creates a funding cliff after 2026, when block grants would need to be re-appropriated

Years 2020–2027: Importantly, the block grant funding appropriated in the bill ends after 2026. While funding for 2027 and beyond may be appropriated in the future, the bill currently creates a block grant funding cliff in 2027. The ability of the Congress to appropriate additional funding is uncertain and could be constrained by the need to offset the cost. As such, by 2027, states would see significantly larger declines in funding compared to current law, with 39 states and DC facing funding cuts, and 18 states with reductions of greater than $10B. By 2027, only 11 states would see an increase in funding under GCHJ compared to current law (Figure 2). The bill is projected to reduce total federal funding to states by $489B through 2027.

“The bill creates a financial incentive for states to direct coverage to very low-income residents near or below the poverty line, potentially at the expense of lower-middle-income individuals who currently receive exchange subsidies,” said Chris Sloan, senior manager at Avalere.

Years 2020–2036: Finally, given the long-term impacts of the Medicaid per capita caps, particularly the shift to lower per capita cap growth rates in 2025, and lack of block grant funding beyond 2026, all states would see a reduction in federal funds relative to current law by 2036 (Figure 3). Federal funding reductions range from $4B in South Dakota to $800B in California.

“A combination of slower Medicaid per-capita cap growth rates and the sunsetting of block grant funding would lead to substantial reductions in federal funds going to states through 2036,” added Chris Sloan, senior manager at Avalere. “The largest negative funding impacts of this bill to states are outside the current 10-year budget window.”

The bill includes additional changes to state insurance markets by allowing states to apply for waivers of key ACA provisions

In addition to the funding changes, the bill gives states the option to include a waiver in their block grant application that allows the state to waive the ACA’s market rules. States are given the option to waive age rating rules, essential health benefits, the prohibition on medical underwriting, and the required medical loss ratio for plans and enrollees who receive some benefit from the state’s block grant funding. While this analysis does not attempt to project which states will pursue a waiver, nor which of the ACA’s market rules states will attempt to waive, previous Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analyses have projected the expected impacts of waivers. CBO previously estimated that similar flexibilities to those in GCHJ would lead to lower average premiums, largely due to the reintroduction of medical underwriting and coverage of fewer services, and potentially higher enrollment in some states. However, CBO also projected this flexibility to substantially increase costs of those individuals with significant medical costs and those who would be at risk of medical underwriting.

Funding for this research was provided by The Center for American Progress. Avalere maintained full editorial control.

Appendix

Effect on ACA Population

GCHJ legislation would use block grants starting in 2020 to allow states to fund coverage expansion (i.e., Medicaid expansion and BHP) and insurance affordability programs (i.e., premium tax credits and CSR payments).

Block grant funding would be below current federal funding levels under the ACA for Medicaid expansion states, and would end after 2026. Beginning in 2021, funding would be distributed primarily based on each state’s share of population with incomes between 50 and 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), a range that excludes a significant proportion of people who qualified for exchange premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions.

Starting in 2024, block grant amounts would be partially determined by the state’s enrolled population in credible coverage-defined as having an actuarial value at least equivalent to the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) actuarial value; effectively, coverage that has very low-cost sharing and premiums, similar to Medicaid and CHIP today. As such, funding would effectively be allocated according to the number of a state’s 50% to 138% FPL population the state enrolls in coverage that is equivalent Medicaid and CHIP.

Under the block grants, funding for the coverage expansion programs under the ACA would be reduced, compared to current law, by $95B, or 7%, from 2020 through 2026. From 2020 to 2027, the first year for which there is no appropriated funding, the federal funding to states would be cumulatively reduced by $326B, or 21%. From 2020 to 2036, that reduction relative to federal law is projected to grow to $3,071B, or 71%.

Effect on Traditional Medicaid Population

For those who would have historically been covered by Medicaid prior to ACA expansion, federal Medicaid funding would convert to a per capita allotment in 2020 and beyond. Through 2024, the inflation factor would be the consumer price index for medical care (CPI-M) +1 for elderly and disabled and CPI-M for children and adults. After 2024, the inflation factor would be CPI-M for elderly and disabled and the consumer price index for all urban consumers (CPI-U) for children and non-disabled adults. CPI-U measures economy-wide inflation and typically rises at a slower rate than Medicaid spending growth. Therefore, tying allotment to CPI-U is projected to lead to significantly lower Medicaid funding for the non-expansion Medicaid population.

Under the per capita caps, funding to states would be reduced, compared to current law, by $120B, or 4%, from 2020 through 2026. This grows to $164B, or 5%, from 2020 to 2027 and $1,079B, or 12%, from 2020 to 2036.

Different Incentives under GCHJ

The bill’s formula allocates block grant funding to states solely based on insurance coverage for the population between 50% to 138% FPL. States are allocated funding according to the number of individuals and those enrolled in credible coverage in that income range. As such, states have a strong incentive to focus their block grants on covering that population, as it leads to additional funding for the state. Conversely, the funding formula does not take into account the number of individuals, enrolled in coverage or otherwise, above 138% to 400% FPL who have been traditionally enrolled in exchange coverage and eligible for premium and cost sharing subsidies.

Methodology

Current Law Projections Methodology

To conduct the analysis, Avalere used the Congressional Budget Office’s latest September 2017 baseline for Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65: 2017 to 2027 to project federal spending on the ACA’s advance premium tax credits, cost sharing reductions, and basic health program through 2027. This created the baseline of expected federal spending for these programs. Avalere then allocated the projected current law federal spending by state using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) 2017 Open Enrollment Period State Level Public Use file to determine the average subsidies by state. Avalere then multiplied those by total number of enrollees by state and determined the proportion of spending, for each of the three programs, attributable to each state. For purposes of this analysis, Avalere assumed that relative distribution of enrollees between states remained the same through 2027. For projections through 2036, Avalere assumed that the average historical growth rate for advance premium tax credits, cost sharing reductions, and the basic health program continue.

For expected current law Medicaid spending, Avalere projects federal funding by state using the 2016 CMS Medicaid Actuarial Report to forecast per-enrollee spending by basis of eligibility group and U.S. Census Bureau state populations projections by age group to forecast enrollment growth by state and basis-of-eligibility. Avalere used CBO’s 20176 baseline and assumptions for federal Medicaid spending and enrollment, as well as medical and economy-wide inflation.

Importantly, CBO assumes future states expand Medicaid. For purposes of this analysis, Avalere does not assume additional states expand, given the limited information available to predict state decisions and the outputs of this analysis providing information at the state level.

Graham-Cassidy-Heller-Johnson Bill Projections Methodology

To project the funding available under GCHJ, Avalere used the latest bill text available on the Cassidy Senate website as of September 18, 2017. For purposes of determining the state 2020 baseline funding amounts available to each state, Avalere grew each state’s 2017 premium subsidy, cost sharing reduction, and basic health program spending forward by CPI-M until 2020, using the CMS 2017 Open Enrollment Period State Level Public Use. Similarly, to determine the base for the Medicaid expansion population, Avalere used the total spending for the first quarter of 2016, extrapolated to a year, from the CMS 64 Total Medical Assistance Expenditures VIII Group Break Out Report from June 2017.

Avalere also modeled the distribution of the $15B stability funding available for 2020, the $6B available in 2020 for low-density and non-expansion states, and the $5B available in 2021 for low-density and non-expansion states. For purposes of distributing this money, Avalere distributed it to eligible states according to their relative share of the 50% to 138% FPL population.

Importantly, the bill text specifically uses 45% to 133% FPL as the range for distributing the funds. However, given the modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) 5% de minimis, Avalere used 50% to 138% FPL. This is in line with the public statements and analyses from the bill’s authors.

For purposes of determining the distribution of funds linked to the population in each state from 50% to 138% FPL, Avalere assumes that the current state distribution, as determined by the most recent 2016 American Community Survey (ACS) data remains stable through 2036. Avalere does not attempt to project state level shifts in poverty.

Avalere was required to make additional assumptions for purposes of determining the number of individuals in each state enrolled in credible coverage from 50% to 138% FPL. Starting in 2024, the formula incents states to offer credible coverage to individuals in this income group. However, states have historically had substantially different reactions to offers of federal funds to cover this population. Additionally, Avalere is not attempting to project which states implement programs to more aggressively cover this population. To provide a proxy, Avalere assumed that the distribution of coverage of these individuals between states will be similar to the 2016 state Medicaid coverage of these individuals. As such, Avalere used the 2016 ACS data on the number of individuals in that income range who had coverage to determine the allocation of these funds between states under the GCHJ block grant formula.

The bill provides states with the option to receive a 5% advance of their 2026 funding in 2020. For purposes of this analysis, Avalere does not assume states utilize that options. Additionally, Avalere does not model the risk adjustment mechanism or state level adjustments to account for higher or lower relative healthcare costs between states. As such, this analysis may underestimate the amount of funding available to states like Alaska, which have substantially higher average healthcare costs than other states. However, as the bill does not provide specific formulas or instructions on how these adjustments will be made, Avalere does not include them in the analysis. Additionally, Avalere does not include disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, neither the cuts nor the non-applicability to low-grant states, in its analysis.

As the bill does not appropriate block grant funding to states after 2026, Avalere does not assume any state block grant funding available from 2027 onward. For the Medicaid per capita caps, Avalere’s forecast for this analysis for the years beyond 2026 extends the CMS per enrollee growth projections and Census Bureau state population projections.