Understanding the History and Use of the Accelerated Approval Pathway

Summary

Amid recent policy focus on the accelerated approval pathway and questions regarding the pathway’s evidentiary standards and decision framework, Avalere reviewed the history, process, and use of this pathway to date and the potential future use of accelerated approval for pipeline products.The Accelerated Approval Program was developed in 1992, largely in response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s after advocates urged the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) to streamline efficacy requirements to expedite access to innovative products that show promise for serious, incurable diseases. At the time, researchers were advancing the idea of using surrogate endpoints as a tool to demonstrate drug value and an improvement in patient outcomes. A surrogate endpoint is a clinical trial endpoint substitute for a “direct measure of how a patient feels, functions, or survives.” Surrogate endpoints may be used when clinical outcomes take a long time to study or in situations where the surrogate endpoint is well recognized as predicting long-term clinical benefit.

In 1992, the FDA issued a final rule that established the Accelerated Approval Program (21 CFR Subpart H) with the intention of allowing for the expedited approval of drugs that treat serious conditions and “fill an unmet medical need” using a surrogate endpoint. Twenty years later, Congress codified the pathway via the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA).

Overview of the Accelerated Approval Program

The FDA uses the same basic standards for approving drugs via the Accelerated Approval Program and the traditional pathway. Accelerated approval drugs are assessed against the statutory “substantial evidence of safety” standard to determine if sufficient information demonstrates “a drug is safe for use under conditions prescribed, recommended or suggested in the proposed labeling.” Additionally, drugs must meet the FDA’s standard for effectiveness, which requires substantial evidence based on “adequate and well-controlled clinical investigations.”

Approval under the accelerated approval pathway allows for the marketing and patient use of the product. However, these products are limited by the requirement that sponsors produce data establishing that the surrogate endpoint or intermediate clinical endpoint is “reasonably likely” to predict a drug’s intended clinical benefit. Sponsors must also agree to conduct a post-marketing confirmatory study or studies to verify and describe the relationship between the endpoint and the expected clinical benefit (Figure 1).

If confirmatory trials do not verify the clinical benefit of a drug or do not demonstrate sufficient clinical benefit to justify the risks associated with the drug, then the drug’s approval may be withdrawn (21 CFR 314.530) or the label indication of the drug adjusted.

Use of the Accelerated Approval Pathway to Date

As of June, 269 drugs and biologics have been approved by the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) via this route. According to an analysis of CDER data conducted by the National Organization for Rare Disorders, from 1992 through 2010 the pathway was primarily used to approve drugs to treat HIV (39.7% of approvals), cancer (35.6%), and other rare disease (24.7%). Since then, the use of accelerated approval has shifted focus to oncology drugs. 85% of accelerated approvals from 2010 to 2020 were for oncology indications.

Compared to traditional approval, the accelerated approval pathway has brought therapies to market several years sooner. For example, a 2011 study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found that oncology products approved via the pathway were brought to market 4.7 years faster than traditionally approved oncology products, representing a significant decrease in the time to bring a drug to market.

A large number of accelerated approval drugs have gone on to receive full approval; however, others that failed to demonstrate clinical benefit have been withdrawn. In a review of accelerated approval drugs approved between 1992 and 2016, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review found that 76.5% have converted to traditional approval, 10.3% were withdrawn, and 13.1% of approved drugs were reported to have been on the market a median of 9.5 years without confirmatory evidence to warrant traditional approval (Figure 2).

Source: Institute for Clinical and Economic Review.

Recent Policy Focus on the Accelerated Approval Pathway and Implications for the Product Pipeline

While there is support for the accelerated approval pathway as a way to bring therapies to the market more quickly than under traditional approval, some stakeholders have expressed concern that standards are not stricter around the timeline for manufacturers to complete post-marketing requirements or to sunset accelerated approval status. In addition, there is discussion regarding the cost of accelerated approval products, and questions around whether a drug’s cost correlates with value given limited clinical data.

As a result of recent scrutiny on the pathway, several stakeholders have proposed changes to the pathway or proposed modifying drug payment for accelerated approval drugs. For instance, in their June Report the Congress, the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission recommended increasing Medicaid rebates for accelerated approval drugs until confirmatory trials were completed, although other stakeholders have opposed this approach due to its potential impact on patient access for conditions with unmet medical need. With the approval of aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease in June, questions reemerged about the FDA’s role in assessing product benefit in situations where initial clinical evidence may be limited. In August, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General launched a review of the FDA’s use of the accelerated approval pathway as it relates to the aducanumab approval.

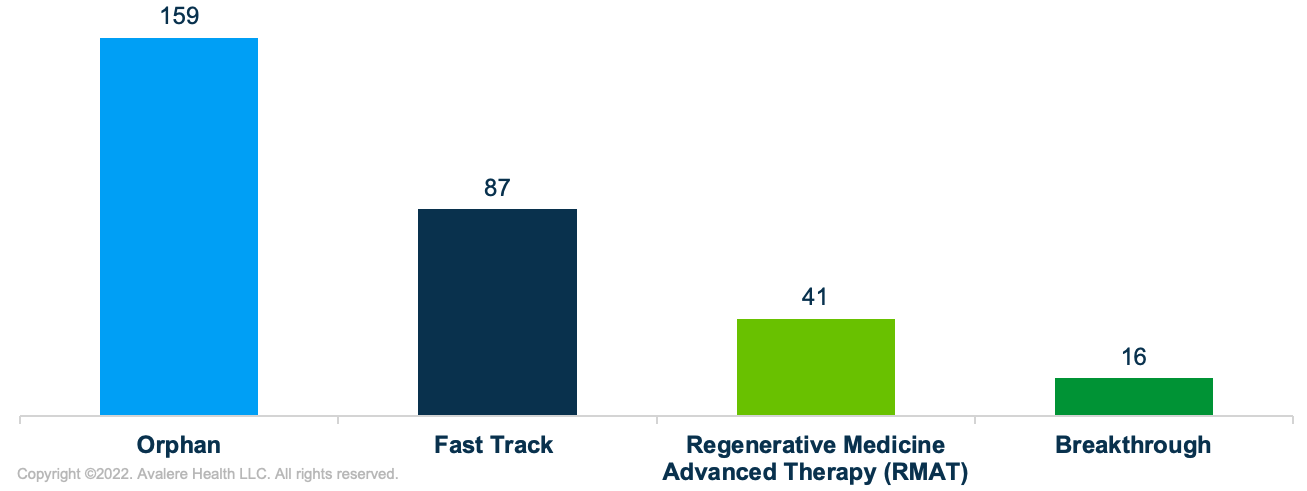

At the same time, the accelerated approval pathway may become more relevant for pipeline therapies coming to market in the next decade, including many cell and gene therapies. Similar to products that have historically been approved through the accelerated approval pathway, many therapies in the pipeline are also products intended to treat rare diseases with unmet medical need. Specifically, Avalere examined about 200 unique products in the Phase I, II, and III pipeline, including therapies with special FDA designations (i.e., orphan drug designation, regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT), breakthrough therapy, fast track, and priority review) and therapies determined to be administered in one or a few administrations (Figure 3).1 Many of these therapies are being developed to treat rare and serious conditions such as rare cancers, muscular dystrophy, hemophilia, and sickle cell anemia. In fact, about 80% of all pipeline therapies analyzed have orphan drug designation from the FDA.

Given the possibility for reform and the potential for increased relevance of the accelerated approval pathway, stakeholders should monitor FDA and policymaker activity related to the pathway and assess potential impact to pipeline product and business priorities.

Funding for this research was provided by the Biotechnology Innovation Organization. Avalere retained full editorial control.

To receive Avalere updates, connect with us.

Note

- Avalere’s analysis only included Phase I, II, and III pipeline therapies with any special FDA designations (orphan, breakthrough, RMAT, fast track, or priority review). Analysis excluded any infectious disease products and vaccines (except cellular therapy vaccines), pain management products, including antihistamines, diuretics, and contraceptives, maintenance treatments or chronic therapies, therapies without a unique mechanism of action, and bioengineered parts. Analysis also excluded any oral, sublingual, topical or subcutaneous injections, unless the product was a cellular or gene therapy.

January 23, 11 AM ET

Learn More