Policy Issues, Part 1: Promoting Health by Addressing Food Insecurity

Summary

Various national and local health policies aim to address food insecurity through both healthcare and community-based programs.While increasing attention from the media and public health advocates has raised awareness of this problem in recent years, further progress in healthcare policy is needed to fully acknowledge and address the links between food insecurity and poor health outcomes. Additionally, a wide variety of health plans, provider networks, and national corporations must continue to innovate and develop strategies to adapt to this trend.

Background on Food Insecurity

The US Department of Agriculture defines food insecurity as a “lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life.” In 2018, an estimated 1 in 9 Americans was food insecure, equating to more than 37 million Americans. Food insecurity is influenced by various factors, including household income, employment, racial and ethnic disparities, disability, and critical household expenses (such as caring for an ill child). Although poverty and food insecurity are closely related, not all people living below the poverty line experience food insecurity, and people living above the poverty line can also be food insecure.

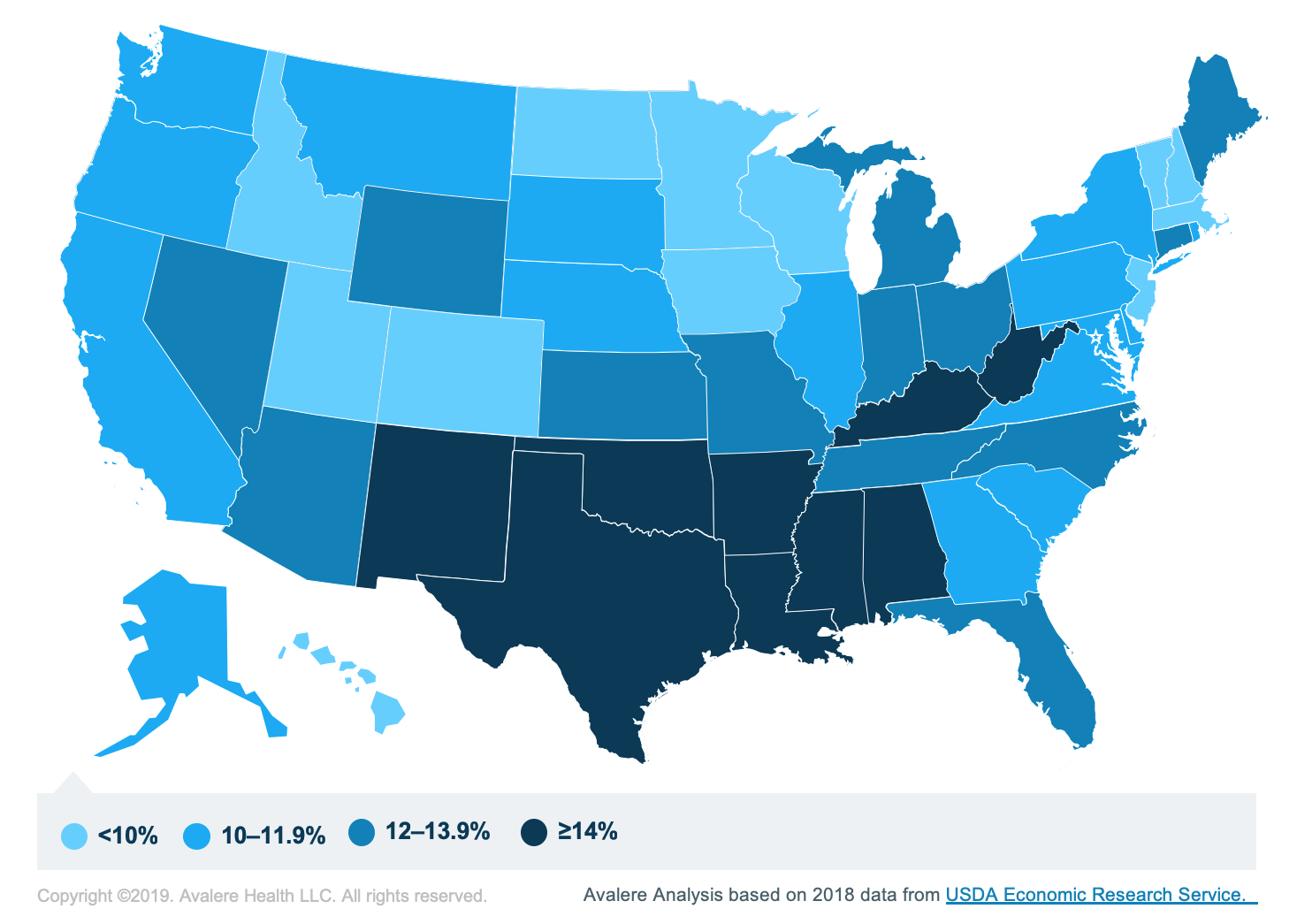

The following chart shows the proportions of households with food insecurity by state in 2018:

Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes

Food insecurity can contribute to or exacerbate nutrition deficits that are linked to chronic conditions and diseases. Children could experience pronounced malnutrition, growth stunting, obesity, anemia, or cognitive problems. Seniors may experience impaired quality of life, immunity, and management of preexisting conditions. People living with food insecurity are also likely to have increased healthcare expenditures. A 2018 study showed that food-insecure households spend about 45% more ($6,100) annually on medical care than do food-secure households ($4,200). Limited financial resources may drive them to underuse medications, postpone or forgo preventive or interventional medical care, and purchase cheap and nutrient-poor food. These trade-offs increase the risk of obesity and diabetes, among other diseases.

A recent cross-sectional study by Fraze et al. found that only about 25% of hospitals and even fewer physician practices screen for food insecurity and other social determinants. The rate was higher among practices that have more insurance coverage for disadvantaged patients, such as those in Medicaid expansion states and those receiving more Medicaid revenue. The authors of this research also noted that organizations with payment reform models were more likely to screen, while “misaligned incentives” were a major barrier for others.

Pertinent Policies

Public policies spanning from agriculture to healthcare play a role in addressing dietary quality, food insecurity, and improved health outcomes. Medicare and other health plans are increasingly expanding opportunities to address food insecurity. A recent study published in JAMA Internal Medicine estimated that 10% of Medicare beneficiaries are food insecure. Earlier in 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded the definition of Medicare Advantage supplemental benefits. This enables plans to think creatively about ways to address food insecurity, including produce prescriptions or the delivery of medically tailored meals as a healthcare intervention. Also, a recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that that Medicaid programs administered in 40 states now incorporate activities related to social needs (including food insecurity) through managed care contracts or Section 1115 demonstration waivers. North Carolina, for example, requires managed care organizations to refer patients to such services and track outcomes. While private payers are beginning to experiment, the need to better address social needs remains, given that the study by Fraze et al. suggested they less consistently monitor food insecurity than do public insurance programs.

A recent article in Kaiser Health News brought attention to the simultaneous and synergistic problems of malnutrition and food insecurity among America’s aging senior population. The Older Americans Act has funded home-delivered and group meals (among other services) for anyone age 60 and above since 1972. Recently, funding has fallen short, due to a growing senior population and economic inflation, decreasing the availability of this program that serves as a lifeline to about 1.6 million seniors.

Other national policies—particularly the farm bill—play a prominent role in public responses to food insecurity. More than 75% of the farm bill’s funding (roughly $71 billion) goes toward the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—formerly known as food stamps—to address food insecurity. It is not tied to health outcomes, however. The 2018 bill included $25 million for a novel nutrition prescription program for low-income individuals, and many organizations and healthcare providers are partnering to engage in a pilot program to prove a connection between increased fruit and vegetable consumption and improved health outcomes so that the program can expand in future years.

Our Expertise

Avalere Health has a history of working with a variety of key stakeholders interested in better addressing food insecurity to improve health. Last year, we facilitated a meeting among Meals on Wheels America, Aetna, and other key stakeholders to discuss the creation of a pathway to address social needs through flexible benefits. We supported leaders from Aetna and Meals on Wheels America to submit these recommendations—including definitions of benefits, eligibility, and duration—to CMS. Through the Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative, we support many hospitals and healthcare systems around the country seeking to improve the quality of care provided to malnourished patients following their hospital discharge and across transitions of care by sharing best practices, providing research support, and more. Through the creation of quality measures, we are working with our partners to support providers across the country to prioritize management of malnutrition to improve quality of care, and this strategy can also help to ensure food insecurity screening is adequately implemented. Avalere was also recently chosen by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to serve as a Health Systems Transformation Research Coordinating Center to align evidence-building activities to transform health systems and accelerate the spread of innovative solutions and research addressing interrelated clinical and social needs, with emphasis on Medicaid-eligible individuals and systems serving them. Our team has expertise including data analysis, alternative payment models, clinical and public health nutrition, food and health policy, and other fields that inform our work in this area.

We look forward to continuing and expanding this important work with more partners. For more information on how we assist our clients in evaluating their opportunities and risks in addressing food insecurity, connect with us.

Find out the top 2020 healthcare trends to watch.

January 23, 11 AM ET

Learn More