CMS HCC Risk Adjustment Model 2019: Winners & Losers

Summary

Our analysis finds there will be winners and losers at the plan level under the new models.Executive Summary

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) uses risk-adjustment models to determine capitated payments made to Medicare Advantage (MA) plans and makes periodic updates designed to improve the performance of the models. A key component of the risk adjustment models is the set of Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC) that CMS uses to determine payments to MA plans.

This study assesses the impact of the most recent changes to the risk-adjustment models. Because 2019 payments will be affected by the changes, it is important for plans to understand now what the potential impact on their reimbursement may be in 2019 based on claims being submitted in 2018. MA plans can use the information provided in this report to better project how and where the changes will most impact their reimbursement based on the profile of their own beneficiary population.

Key Findings

Overall, risk scores in the new version increased only slightly by 0.78% in our study, which is less than the 1.1% projected by CMS. The largest change in community risk scores was a decrease of -0.04 in the full-dual disabled mean risk score. There were insignificant changes in other mean risk scores regardless of gender, age, race/ethnicity, region, or plan type.

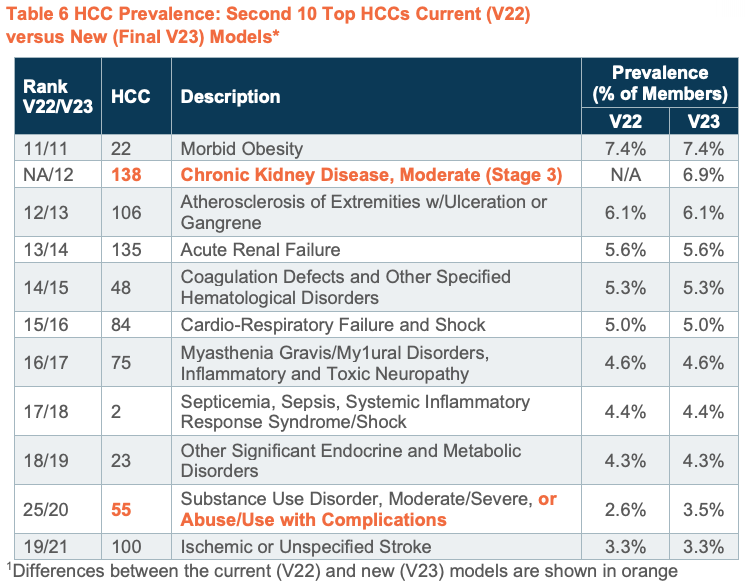

The top-10 most frequently occurring HCCs were identical in the current and final models. One of the new HCCs—HCC 138: Chronic Kidney Disease, Moderate (Stage 3)—had a fairly high prevalence rate of 6.9% (HCC rank #12). The other 3 new HCCs had very low prevalence rates of <0.1% and thus no impact on mean risk scores.

The expanded HCC—HCC 55: Substance Use Disorder, Moderate/Severe, or Abuse/Use with Complications—increased in prevalence from 2.6% to 3.5%, and members who met the expanded criteria had a significant increase in mean risk scores of 0.32. The most striking finding was that members who qualified for HCC 55 only under the new expanded criteria have risk profiles that are nearly 3 times higher than those who qualified under the old criteria, indicating that beneficiaries with the added diagnoses have significantly greater burden of illness, but the new HCC was not associated with an increase in factor weights. The overall effect was a slight decrease in factor weights for this HCC of -0.29%, with larger decreases in the non-dual aged (-3.92%) and full-dual disabled (-2.19%) populations. CMS may want to re-visit this change in future models and consider making beneficiaries with the added diagnoses a separate HCC or some other modification that recognizes the distinct features of the drug and alcohol “poisoning” group.

The proposed new count factor had little impact on mean risk scores. Compared to the current payment model, risk scores with the count factor included were identical for patients with 0–3 HCCs, slightly lower for patients with 4–5 HCCs, and slightly higher for patients with 6 or more HCCs. The largest increase was for beneficiaries with 10 or more HCCs, but their prevalence in the population was only 3%.

There were more significant changes at the health plan level, with winners and losers. The majority of plans (79%) showed an increase in mean risk score ranging from +0.005 to +0.023 (0.31% to 1.8%) while mean risk scores were lower for 5 plans ranging from -0.019 to -0.003 (-0.96% to -0.18%).

Importantly, even small changes in risk scores can have a significant impact on reimbursement. For example, using an average bid rate of $800, a 0.01 increase in mean risk scores translates to $8 per member per month (PMPM). For the average size plan in our study (n=45,760 members), this equates to a potential reimbursement increase of $4.4M per year. Given the average risk-score variation we observed among plans in the study ranging from -0.019 to +0.023, the average plan could see changes in reimbursement ranging from a decrease of $8.3M to an increase of $10.2M.

Conclusions

Although the overall average impact of the proposed changes was small, there were winners and losers at the plan level. MA plans with more beneficiaries in the impacted populations—such as plans serving a large number of dual-eligible disabled beneficiaries or more members with the impacted HCCs—could see substantial changes in risk scores and payments in 2019.

Background

The CMS uses a risk-adjustment process to determine capitated payments made to MA plans. A key component of the risk-adjustment models is the set of HCCs that CMS uses to determine payments to MA plans. The HCC risk-adjustment models aim to predict what a MA plan enrollee’s monthly cost to the plan will be in the following year based on the enrollee’s demographic characteristics (i.e., age and gender) and health status in the current year. Health status is incorporated based on an algorithm that categorizes 79 HCC conditions and selected HCC combinations known to materially impact the cost of care using member’s documented diagnosis codes.

Risk scores are calculated using different sets of weights (model coefficients) depending on the group of beneficiaries or segment to which a member is assigned. There are currently 9 distinct segments (see below). HCC weights are estimated separately for each segment to reflect the unique cost and utilization patterns of beneficiaries within the segment. This study analyzed the impact of the proposed changes on the 6 continuing community segments.

Proposed Changes to the HCC Risk-Adjustment Models for the 2019 Payment Year

The Advance Notice issued in December 2017 described several proposed changes to the risk adjustment models for the 2019 payment year.

Adding 4 new HCCs

-

-

- HCC 56: Substance Use Disorder, Mild, Except Alcohol and Cannabis

- HCC 58: Reactive and Unspecified Psychosis

- HCC 60: Personality Disorders

- HCC 138: Chronic Kidney Disease (Stage 3)

-

Broadening the definition of 1 HCC

-

-

- HCC 55: Add selected drug/alcohol “poisoning” (overdose) ICD codes to create “Substance Use Disorder, Moderate/Severe, or Substance Use with Complications”

-

Adding a factor to account for the number of chronic conditions for each beneficiary

-

-

- CMS compared the predictive power of 2 different count factor models: 1) a model that counts only the conditions that result in a payment; and 2) a model that counts all conditions, regardless of whether they are used for payment

- Only the payment condition count model materially improved predictions so that is the model examined in this report

-

Re-calibrating all HCC risk models after inclusion of the new factors

-

-

- Even though an HCC is included in both the current and the proposed models, the contribution it makes to the overall risk score (called its “relative factor”) may change as model HCC weights are re-calibrated after the changes are incorporated

-

The CMS Final Call Letter issued in April 2018 indicated the model changes described in the Advance Notice will be implemented with the exception of the condition count factor, which will be deferred for another year. This analysis assumes the Final V23 payment model is applied 100%. Based on the 2019 announcement, the new model without the count factor will contribute 25% of the risk score calculated, with 75% of the risk score from the V21 model.3 The analysis also assumes EDS and RAPS are fully synchronized. Further analyses at the individual plan level could provide more accurate predictions of the actual effect on individual contracts.

Study Population

We used enrollment, medical, and pharmacy data from Inovalon’s Medical Outcomes Research for Effectiveness and Economics Registry (MORE² Registry®). The MORE² Registry® is a data warehouse that contains longitudinal patient-level medical and pharmacy claims data for more than 240 million unique individuals enrolled in commercial, Medicare Advantage, traditional Medicare, and managed Medicaid programs nationwide.

Members were included in the study if they were continuously enrolled in a MA plan for the full year with no more than a 30-day gap allowed to assure members had comparable time in the health plan. Members were required to have Original Reason for Entitlement and Dual Eligible status documented, as these fields are required for risk scoring in the current and proposed models. Members of only a prescription drug plan (PDP) were excluded.

The final study population included 1,098,252 members in 58 individual contracts from 24 MA organizations in 2015.

Data Analysis

We compared HCCs, mean risk scores, and plan payments under the current model (V22), the new model with the count factor included (Proposed V23), and the final 2019 payment model (Final V23).

We calculated HCC prevalence rates as the percentage of the sample population who met the criteria for each HCC for each of the 3 models. Risk scores were compared among the 3 models within each of the 6 continuing community risk-score segments. We also stratified the study sample into various subgroups to evaluate whether the changes had a differential impact based on health plan member or plan characteristics.

See Appendix 1 for details on our method for calculating HCCs and risk scores under the 3 models.

Results

Health Plan and Member Characteristics

The final study population included 1,098,252 members in 58 individual H-contracts from 24 MA organizations that met the inclusion criteria for the study. The average plan size was 45,760 members. The number of members per plan ranged from 25 to over 200,000 (Table 1)

MA beneficiaries were more likely to be female and white with an average age of 72 years (Table 2). The majority enrolled in Medicare at age 65 (75.6%) and were non-dual eligible (82.4%). The distributions by gender, age, race/ethnicity, original reason for entitlement, and dual status were highly representative of MA plans nationally with the exception that the West Census Region was underrepresented in our sample. Similarly, the plans included in the study were representative of MA plans nationwide (Table 3).

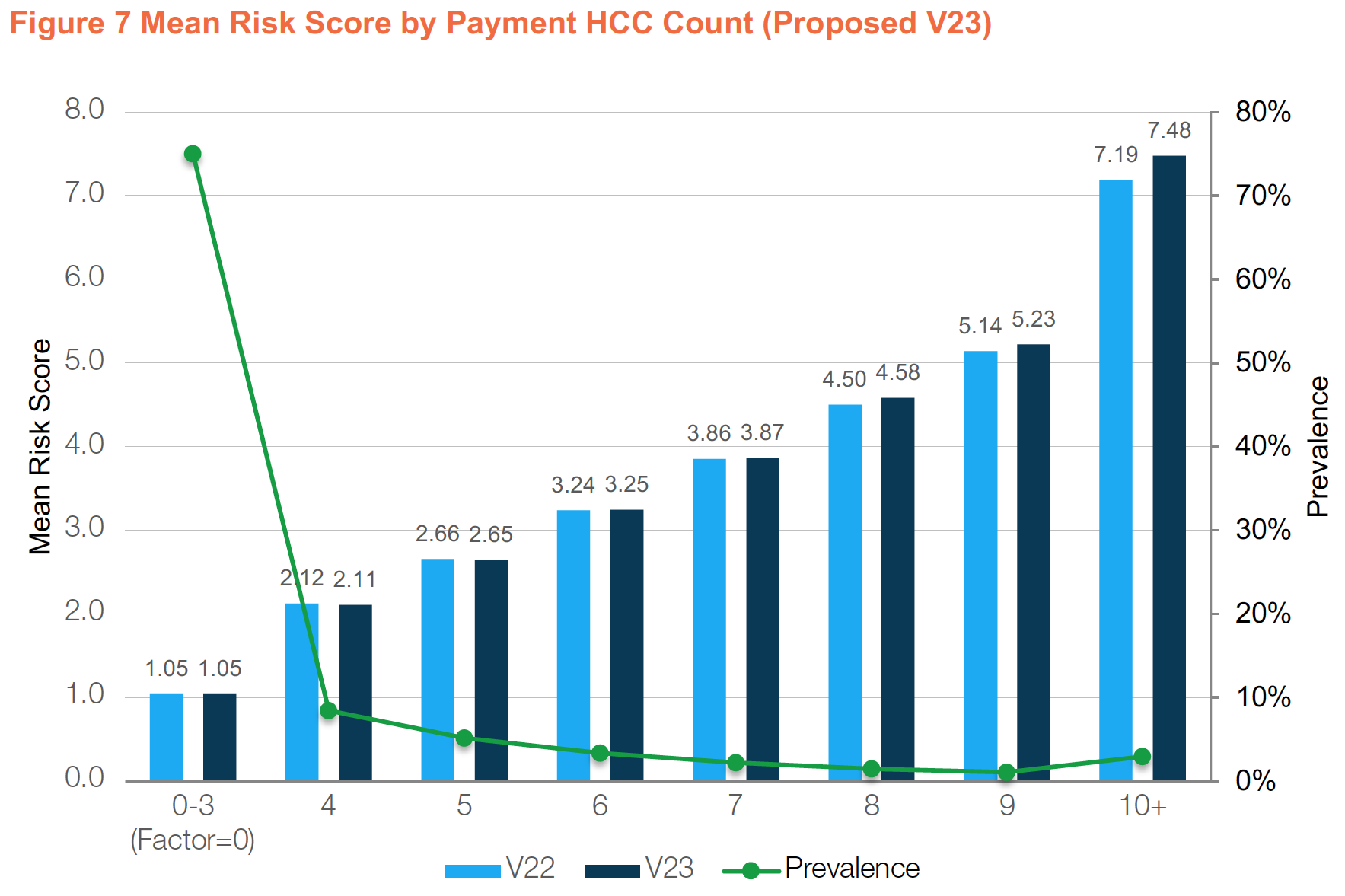

The distribution of the number of HCCs per beneficiary is shown in Table 4. Seventy-five percent of MA enrollees had 0-3 HCCs which has no impact on risk scores in the proposed count factor version. Only 5.6% of beneficiaries had 8 or more HCCs.

HCC Prevalence

The prevalence rates for the top-10 most frequently occurring HCCs were identical in the current and both new models (Table 5). There was a slight shift in the next 10 most frequently occurring HCCs (Table 6). The new HCC 138 ranks 12th, with a prevalence rate of 6.9%. The broadened definition HCC 55 rises from 25th to 20th in rank, but still has a relatively low prevalence rate of 3.5%. The prevalence rates of the other 3 new HCCs were very low (<1%) (Table 7). Since very few members have these new HCCs they will have little/no impact on overall risk scores.

Mean Risk Score Comparisons

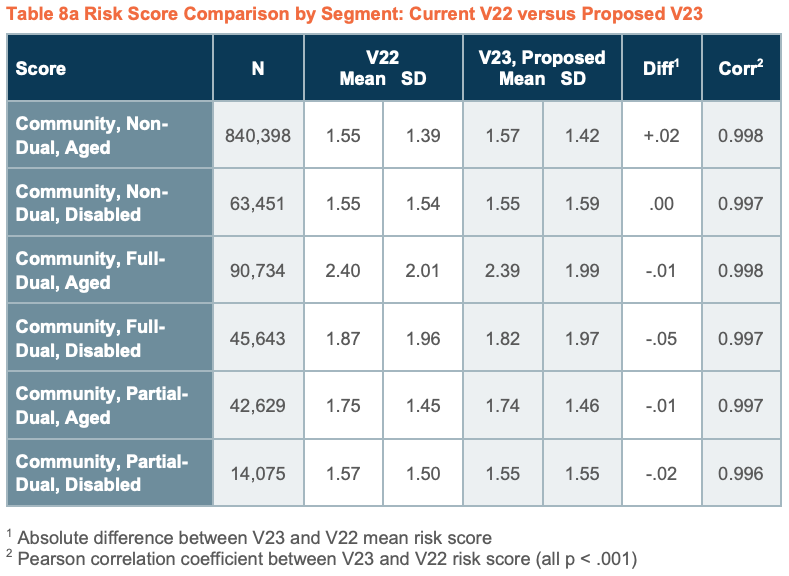

The mean risk scores from the current model (V22) and new model (Final V23) for the 6 community segments are presented in Table 8 (Note: mean risk scores from the proposed version which includes the count factor are shown in Appendix 2, Table 8A). Each member was assigned a score calculated using weights from the appropriate segment based on their age (whether under age 65) and dual status (full, partial, or non-dual).

There were only minor differences in mean risk scores within each segment. The resulting mean risk scores from the 2 versions were almost perfectly correlated with each other (last column) indicating minor changes in risk scores even at the member level. The largest difference was a decline of -0.04 in the mean risk scores in the community, full-dual, disabled segment. This is also the group that tends to have the greatest number of clinical and social risk factors that impact resource utilization and health outcomes.

It is important to understand these are overall averages based on the sample population. Health plans whose age, dual status, or disabled population distributions vary significantly from the overall sample (see Table 2) may show different results depending on their beneficiary population mix as shown in the plan level impact analyses below. For example, plans serving a large full-dual disabled population could see a significant reduction in mean risk scores and payments.

CMS stated in the fact sheet of the Advance Notice that “Overall, while the experience of individual plans would vary, the Payment Condition Count model is projected to increase MA risk scores by 1.1%.”4 Based on our analysis, the projected increase in mean risk scores would be less with the count factor included. When carried out to 4 decimal places, the overall mean risk score in the proposed model which includes the new count factor was only 0.62% higher (1.6552 versus 1.6450) and the mean risk score in the final model was 0.78% higher (1.6578 versus 1.6450).

Average risk scores vary only slightly between the versions when stratified by gender (Figure 1) and age group (Figure 2). Note that the mean risk scores in the new version decreased by -0.02 for the under age 65 group and increased by 0.02 in the age 70 or older age groups. There were also no differences in mean risk score within categories of Race/Ethnicity (Figure 3), Census Region (Figure 4), Plan Type (Figure 5), or EGWP status (Figure 6).

Impact of the Count Factor

An evaluation of mean risk scores in the proposed new model (V23) stratified by count of member HCCs compared to the current model (V22) shows they were identical for patients with 0–3 HCCs, slightly lower for patients with 4–5 HCCs, and slightly higher for patients with 6 or more HCCs (Figure 7, mean risk score on left axis).

The largest increase in mean risk scores was for beneficiaries with 10 or more HCCs (+0.29), but their prevalence in the population is only 3% (Figure 7, prevalence on right axis). Although CMS is not including HCC count factors in the new payment year 2019 models, they have indicated their intent to do so in 2020. CMS should explore other approaches, such as counting individual diagnoses or including non-payment HCCs, to better reflect the burden of multiple chronic conditions on beneficiaries’ healthcare utilization and cost.

Impact of the New and Expanded HCCs

CMS added new diagnosis codes to the existing HCC 55, now labeled “Substance Use Disorder, Moderate/Severe, or Substance Use with Complications.” The prior version of HCC 55 included diagnosis codes related to drug “use”, “abuse”, and “dependence”. The final V23 model added codes for drug “poisoning” (overdose). The “poisoning” codes had not previously been included in any HCC, including HCC 54, Drug/Alcohol Psychosis, which is higher in the hierarchy than HCC 55.

Figure 8 compares risk scores for 3 groups of members: 1) those who did not qualify for HCC 55 under either definition; 2) those who qualified under the current definition; and 3) those who qualified only under the expanded criteria for HCC 55.

Regardless of model version, mean risk scores for members who qualify for HCC 55 are materially higher than for those who do not have the condition (middle cluster versus first cluster in Figure 8). Members who qualified for HCC 55 under the old definition (middle cluster in Figure 8) showed a slight decrease in mean risk scores from the current model (mean = 2.67) and proposed and final new models (mean = 2.66 and 2.64). The decrease was larger under the final model due to the recalibrated weights after removing the count factor included in the proposed model.

The most striking finding was that members who qualified for HCC 55 only under the newly included diagnoses (third cluster in Figure 8) have risk profiles that are nearly 3 times higher than those who qualified under the old criteria (+4.59), indicating that beneficiaries with the added diagnoses have significantly higher burden of illness than members who qualified for HCC 55 under the old definition. For example, beneficiaries who qualified for HCC 55 under the current model had mean risk scores of 2.67 compared to 6.91 for those who would have qualified under the expanded criteria but applying the current model.

The new final model yields a significant added incremental risk score increase of +0.32 (7.23 versus 6.91) or 4.7% higher for beneficiaries who have HCC 55 under the expanded criteria compared to the same group of members who would have met the criteria using the current model due to the shift in weights in the new final model.

To better understand the substantial impact this coding change had on risk scores, we examined the number of HCCs of members in each of the 3 groups in Figure 8. On average, members who qualified for HCC 55 under neither version had 2.7 HCCs, members who qualified under the old criteria had 4.8 HCCs, and those who qualified only under the new “poisoning” criteria had 12.8 HCCs. This indicates that the subset of members who qualify under the new criteria represent a materially more complex clinical profile.

We also found that this increase in clinical complexity, and potentially in the concomitant costs of care, was not associated with an increase in factor weights between V22 and Final V23. The overall effect was a slight decrease in the weight for this HCC of -0.29%, with larger decreases in the non-dual aged (-3.92%) and full-dual disabled (-2.19%) populations (see Appendix 3).

These results indicate that the inclusion of this group in HCC 55 may contribute to an increase in heterogeneity, both in terms of clinical and financial factors. CMS may want to re-visit this change in future models and consider making beneficiaries with the added diagnoses a separate HCC (perhaps adding an interaction term for HCC 55), or some other modification that recognizes the distinct features of the drug and alcohol “poisoning” group.

Members who met the criteria for the added new HCC 138, Chronic Kidney Disease (Stage 3), which had a prevalence rate of 6.9%, had a 6.5% increase in mean risk score (1.87 versus 1.76) compared to the current model (Figure 9). Since the prevalence rates of the other 3 new HCCs was very low (<1%), they had no impact on overall mean risk scores.

Impact at the MA Plan Level

It is important to evaluate the impact of the changes at the health plan level as some plans are more likely to be impacted than others. The absolute difference in mean risk scores between the current models (V22) and new final models (V23) for each of the 24 plans in the study are shown in Figure 10. The majority of plans (n=19, or 79.2%) showed an increase in mean risk score, with mean risk score differences ranging from +0.005 to +0.023 (0.31% to 1.8%). Mean risk scores were lower for 5 plans under the new model, with mean risk score differences ranging from -0.019 to -0.003 (-0.96% to -0.18%). Thus, the range of impact on individual MA plans was from a decline of nearly 1% to an increase of nearly 2%.

Financial Impact

While our analysis found small differences in overall mean risk scores between the current and new models, even small risk score changes can have a significant impact on reimbursement at the plan level. For the sample as a whole, the mean increase was only slightly more than +0.01, and the difference rarely exceeded +0.05 for the various sub-groups examined. However, using an average bid rate of $800, a +0.01 increase in risk score translates to $8 PMPM for a health plan. For the average size plan in our study (n=45,760 members), this equates to a potential reimbursement increase of $4.4M per year.

As noted above, there was also significant variation among plans ranging from -0.019 to +0.023 (Figure 10). Again using the average plan size of 45,760 members, this translates into an annualized reimbursement decrease of $8.3M for plans with the largest reductions in risk scores to an increase of $10.2M for plans with the largest increase in risk scores.

Reimbursement could also vary significantly for plans with a larger proportion of full-dual disabled beneficiaries who had a -0.04 decrease in mean risk scores. For example, assuming that 50% of the average plan size members were in the full-dual disabled segment, the plan could lose $8.8M in reimbursement for those members. While reimbursement levels stay fairly constant on average, there will be winners and losers at the plan level under the new models.

Conclusion

Our analysis of 1.1 million MA beneficiaries from 58 contracts found relatively small changes in mean risk scores for the population as a whole and for various sub-groups of beneficiaries, with no impact on the top-10 most frequently occurring HCCs. The largest change in community risk scores was a decrease of -0.04 in the full-dual disabled mean risk scores. There were insignificant changes in mean risk scores regardless of gender, age, race/ethnicity, region, or plan type.

The new Payment HCC Count factor (deferred until payment year 2020) had little impact on mean risk scores. Three-fourths of members had 3 or fewer HCCs and thus identical risk scores in the two versions, and members with 4-5 HCCs (13.7% of the population) had slightly lower average risk scores. Members with 6 or more HCCs had slightly higher risk scores, but represent 11.2% of the population. The largest change in mean risk scores (+0.29) was in members with 10 or more HCCs, but those members represent only 3% of the MA population.

Although there were 4 new HCCs added to the model, only 1 HCC—128 Chronic Kidney Disease, Stage 3—ranked in the top 20 HCCs (with a prevalence rate of 6.9%). The other new HCCs had very low prevalence rates of much less than 1% (ranging from 0.04% to 0.09%) and had no impact on mean risk scores.

The expanded definition HCC—55 Substance Use Disorder, Moderate/Severe, or Substance Use w/Complications—increased in prevalence from 2.6% to 3.5% of population. However, members who qualified for HCC 55 under the old definition actually had a slight decrease in mean risk scores under the new final model due to the shifts in HCC weights.

An important finding was that the group of members that met the expanded criteria for HCC 55 had much higher mean risk scores of 7.23 compared to mean risk scores of 2.64 (+4.59) using the old definition (but new model weights) and 1.58 for members who do not have HCC 55, indicating members with the newly added diagnoses had significantly greater burden of illness and likely costs. However, the new HCC was not associated with an increase in factor weights overall. CMS may want to re-visit this change in future models and consider making beneficiaries with the added diagnoses a separate HCC or some other modification that recognizes the distinct features of the drug and alcohol “poisoning” group.

In summary, although the overall average impact of the changes were small, even small changes in risk scores can have a large impact on plan reimbursement, and there will be winners and losers as demonstrated in the plan level analysis. Health plans whose memberships are composed of larger proportions of the impacted populations—such as plans serving larger populations of full-dual eligible disabled beneficiaries—could see substantial changes in risk scores and payments.

Appendix 1

We calculated HCCs and risk scores for the current model using the risk adjustment software that CMS makes publicly available for the SAS platform.5 To calculate HCCs and risk scores under the 2 new models, we modified the SAS software as follows:

-

-

- Downloaded and applied the updated the ICD-10 HCC crosswalk table

- Updated the relative factor table using Table 4 of the Advance Notice for the proposed model (V23) and Table VI-1 of the Final Call Letter for the final model (V23)

- Added logic to incorporate factors for HCC counts (proposed model V23 only)

- Revised the hierarchy logic using Table 7 of the Advance Notice (which is identical to Table VI-3 of the Final Call Letter)

- Various other minor code changes to accommodate the new HCCs

-

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

For more information about this report or our analytic capabilities, connect with us.

Find out the top 2020 healthcare trends to watch.

Learn More