Patient Preferences in Triple Negative Breast Cancer Treatments

Summary

To determine the attributes of triple-negative breast cancer treatment that play a direct role in patient treatment decision making at treatment initiation and following initial treatment selection, Avalere conducted focus groups to examine treatment experiences of patients with triple-negative breast cancer and elicit their treatment-related preferences.Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer in women around the world, and metastatic breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death for women in the US.1 Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for approximately 10-15% of all cases of breast cancer2 and is reported in Black women at 3 times the rate as the occurrence in white women.3 TNBC is characterized by the low expression of progesterone receptor, estrogen receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, making it difficult to treat, especially in advanced stages.

Women with TNBC have historically faced poor prognoses and few effective treatment options, but new treatment options for TNBC offer patients the opportunity for increased choice and improved outcomes. In today’s US healthcare system, patient-centered care has been recognized as a key element of high-quality care.4,5 Patient preferences for treatment attributes and components of care from which patients derive value are essential in determining appropriate endpoints for value assessment and for patient-physician shared decision-making. Shared decision-making that incorporates patient preferences has been found to lead to more engaged patients and better patient outcomes.6,7 Healthcare payers and third-party value assessors are increasingly valuing treatments with a greater emphasis on the costs and clinical efficacy of pharmaceutical interventions, and while a movement towards incorporating patient preferences in decision making is seen in numerous value frameworks,8–11 elements of value that patients find particularly salient are often not quantitatively or qualitatively included in the assessment of a treatment’s value.

To determine the attributes of TNBC treatment that play a direct role in patient treatment decision making at treatment initiation and following initial treatment selection, Avalere conducted focus groups to examine treatment experiences of patients with TNBC and elicit their treatment-related preferences.

Methods

Avalere applied a qualitative research design to better understand patient treatment experiences and factors considered in TNBC treatment decision-making. Nine 120-minute focus groups (with 4-6 individuals in each group) were conducted with a total of 45 women who self-reported a TNBC diagnosis. Trained moderators used a semi-structured discussion guide that included both structured and open-ended questions to ensure consistency and continuity across groups.

Participants were required to self-report their TNBC diagnosis, be over the age of 18, have access to an Internet-connected device, and have English language fluency. Demographic information was collected from each via a screener survey. In order to maintain confidentiality, participants reviewed an Information Statement and verbally agreed to participate in the focus group with audio recording.

For each focus group, one Avalere staff member served as the moderator and another recorded field notes and observations. The moderator ensured that questions and concerns about the research study were addressed and that speaking time was distributed among participants.

A general inductive approach for thematic analysis was employed to identify emerging themes from focus group observation notes and reviews of recordings.12–14

Results

Sample Characteristics

Forty-five women with TNBC participated in the focus groups. Sixteen percent were under age 40, and 44% were age 50 or older. The majority of participants identified as White (62%), 33% identified as Black, and 6.7% identified as Hispanic/Latinx (not mutually exclusive). Over three-quarters of participants (78%) earned at least an associate degree, and 67% indicated that they were working full or part time. Most women (67%) had commercial health insurance coverage, either offered through an employer or purchased privately, while 16% had Medicare coverage, 4% were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and the remaining 13% had health insurance through Medicaid or another government program.

Over half (56%) of participants received their initial TNBC diagnosis 2-5 years ago, 22% of participants had been diagnosed in the past 2 years, and 22% were diagnosed between 5 and 26 years ago. Twenty-seven percent of the participants indicated that they had received a metastatic breast cancer diagnosis either upon or since initial diagnosis. Nearly all (96%) participants had received chemotherapy, 87% had surgery, and 67% had radiation. Smaller proportions received immunotherapy (11%) and targeted therapy (4%) (treatments not mutually exclusive). However, 60% of participants had not received treatment in the 90 days prior to their focus group. Table 1 describes the participant sample.

Factors Influencing Initial Treatment Decision Making

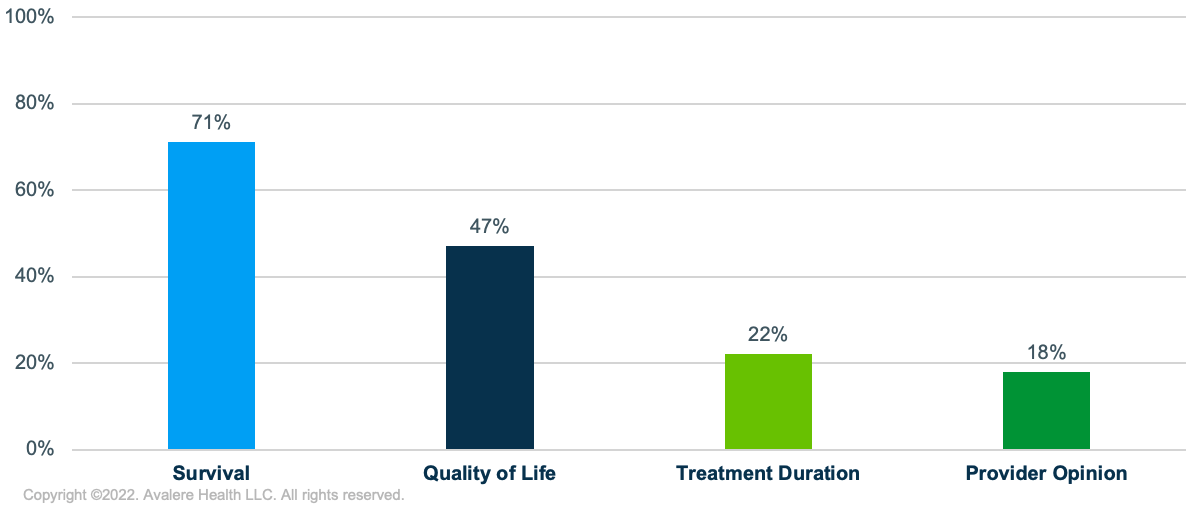

Participants were asked to describe the 3 factors they prioritized during their initial treatment decision making after their initial diagnosis. While most participants who were diagnosed at an early stage expressed that they had limited or no choice in initial treatment per the standard of care, we identified several key factors influencing treatment decision making where there was consensus across focus groups (Figure 1).

- Survival: Participants cited that survival was a top priority. Seventy-one percent of participants mentioned that they considered quantity of life when making their initial treatment decisions.

- Quality of Life: Following quantity of life, 47% of women discussed prioritizing quality of life, which included overall health impacts, results of surgeries, being able to care for children, spending time with family, and continuing to work, among other aspects.

- Treatment Duration: Limiting the duration of treatment was mentioned by 22% of participants as a factor driving treatment choices.

- Provider Opinion: Eighteen percent of participants discussed their provider’s medical opinion and trusting their care teams as factors in their initial treatment decision making.

Of note, side effects communicated by their care team prior to treatment initiation were discussed by participants, but as 1 woman said, “side effects are a consideration, but the question of living is more important.” Although most participants reported that side effects had little influence on their initial treatment decisions, some shared that the side effects they experienced from initial treatment impacted later treatment desires. Many participants reported feeling blindsided by side effects of treatment that were not mentioned by their providers.

Cost of direct cancer treatment was not mentioned as a factor in treatment decision making. After the moderator asked specifically about any cost barriers, many women cited that although their cancer treatments were covered by their insurance, supportive or follow-up treatments were often required. Such treatments might include cold capping to prevent hair loss and neuropathy during chemotherapy, physical therapy following surgery, and treatments for lymphedema, which were often cost prohibitive or required expensive out-of-pocket payments.

Looking back on their initial treatment for TNBC, several Black participants wished they had been informed that certain therapies have different side effect profiles and that tumors can respond differently in people of different races, which may have influenced treatment-related considerations.

Factors Influencing Follow-Up Treatment Decision Making

Participants were asked if their considerations for treatment choice changed after their initial treatment(s) were completed. They described a range of other factors that influenced their initial and subsequent treatment decisions to varying degrees, which included qualities of their care team, characteristics of their treatment site, and clinical and quality of life impacts (Figure 2). Some of these decision-making factors were informed by negative experiences with their care teams. Several participants reported that their clinicians diminished their cancer experiences, some younger participants expressed their clinicians were insensitive to and had poor communication around fertility concerns, and multiple women reported diagnostic or surgical mistakes that drove them to seek other treatment settings.

Repeatedly, participants highlighted the following priorities in their subsequent treatment decision making:

- Mental Health and Support Services: Sixteen participants emphasized that their mental health became a priority. Several described gaps in mental health and support services within their care teams. Participants expressed the need for support in coping with experiences, such as the trauma of diagnosis and treatment, the isolation they felt throughout treatment and recovery, losing a part of their female identity, and fear and anxiety about possible recurrence.

- Patient Support Groups: Participants who had found in-person and online support groups described their satisfaction with and appreciation for the solidarity and advice they received in those environments. Some participants explained that support groups also provided an opportunity to learn about treatment options that may not be typically offered by their care team.

- Patient Education: Nine participants also described that when it came time to make additional treatment decisions (past their initial treatment), they understood and were more educated on available treatment options, took into consideration their treatment experiences thus far, and were better equipped to ask questions of their care teams or seek second opinions.

Importantly, 2 participants shared that they started their own advocacy group after identifying gaps in resources, emotional support, and race-informed care specifically for Black and Hispanic women with TNBC.

Figure 2. Additional Factors Influencing TNBC Treatment Decision Making

Frequently Considered

- Trust in care team

- Support from family

- Second opinions

- Ability to stay active

- Reputation of treatment facility

- Treatment offerings and education specific to race

Moderately Considered

- Proximity to treatment facility

- Understanding the options presented

- Reducing the risk of recurrence

- Minimizing impact of side effects

- Fertility (among women of child-bearing age)

Rarely Considered

- Communicated side effects

- Treatment costs

Conclusions

Qualitative research consisting of focus groups with 45 women with TNBC revealed survival as the most important factor in treatment decision making. There was also consensus among participants to survive their diagnoses with as high of a quality of life as possible, despite potential side effects. Participants recommended that TNBC patients receive increased professional and accessible mental healthcare integrated into their cancer treatment to address gaps in TNBC care and suggested participation in peer support groups to discuss and learn from each other’s experiences with treatment.

Download this content as an infographic.

This research was funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc., and conducted by Avalere Health.

To receive Avalere updates, connect with us.

| TNBC Participant Cohort | Participants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group | ||

| <40 years | 7 | 15.6% |

| 40–49 years | 18 | 40.0% |

| ≥50 years | 20 | 44.4% |

| Race/Ethnicity (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| White | 28 | 62.2% |

| Black/African American | 15 | 33.3% |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 3 | 6.7% |

| Level of Education | ||

| High school graduate or GED | 2 | 4.4% |

| Some college, no degree | 8 | 17.8% |

| Associate’s degree (e.g., AA, AS) | 5 | 11.1% |

| Bachelor’s degree (e.g., BA, BS) | 12 | 26.7% |

| Some post-graduate studies, no degree | 2 | 4.4% |

| Graduate degree or higher | 16 | 35.6% |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed full or part time | 30 | 66.7% |

| On disability leave | 5 | 11.1% |

| Retired | 4 | 8.9% |

| Unable to work | 4 | 8.9% |

| Other | 2 | 4.4% |

| Income Level | ||

| $24,999 or less | 6 | 13.3% |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 13 | 28.9% |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 12 | 26.7% |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 5 | 11.1% |

| $150,000 or more | 9 | 20.0% |

| Location of Residency | ||

| Urban | 11 | 24.4% |

| Suburban | 27 | 60.0% |

| Rural | 7 | 15.6% |

| Cohabitants (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| Parent(s)/parent(s)-in-law | 5 | 11.1% |

| Spouse/partner | 28 | 62.2% |

| Child(ren) | 25 | 55.6% |

| Sibling(s)/other family | 6 | 13.3% |

| Roommate(s) | 1 | 2.2% |

| Self only | 5 | 11.1% |

| Health Insurance Status | ||

| Privately purchased commercial health insurance | 3 | 6.7% |

| Commercial health insurance offered through an employer | 27 | 60.0% |

| Medicare (including Medicare Advantage) | 7 | 15.6% |

| Medicaid | 5 | 11.1% |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 2 | 4.4% |

| Other government program (e.g., TRICARE, VA, OPM) | 1 | 2.2% |

| TNBC Staging | ||

| Never received information about cancer stage | 1 | 2.2% |

| Currently early stage | 24 | 53.3% |

| Early stage at diagnosis that has progressed to late stage or advanced | 6 | 13.3% |

| Late stage or advanced when first diagnosed | 13 | 28.9% |

| Not sure | 1 | 2.2% |

| Metastatic disease at or following initial diagnosis (standalone question) | 12 | 26.7% |

| Treatments Received in Prior 90 Days (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| Surgery | 3 | 6.7% |

| Radiation | 3 | 6.7% |

| Chemotherapy | 11 | 24.4% |

| Immunotherapy | 4 | 8.9% |

| Targeted treatment | 4 | 8.9% |

| None | 27 | 60.0% |

| Treatments Ever Received (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| Surgery | 39 | 86.7% |

| Radiation | 30 | 66.7% |

| Chemotherapy | 43 | 95.6% |

| Immunotherapy | 5 | 11.1% |

| Targeted treatment | 2 | 4.4% |

| Treatment offered through a clinical trial | 4 | 8.9% |

| Location of Treatment Received (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| Hospital that is part of a university/medical school | 29 | 64.4% |

| A local community hospital | 13 | 28.9% |

| Doctor’s or other health care provider’s office or clinic | 13 | 28.9% |

Notes

- Wolfe, A. “Institute of Medicine report: crossing the quality chasm: a new health care system for the 21st century.” Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice 2.3 (2001): 233–235.

- Epstein, R.M., et al. “Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care.” Health Affairs 29.8 (2010): 1489–1495.

- Barr, P., G. Elwyn, and I. Scholl. “Achieving patient engagement through shared decision‐making.” The Wiley Handbook of Healthcare Treatment Engagement: Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice (2020): 531–550.

- Greenfield, S., S. Kaplan, and J.E. Ware Jr. “Expanding patient involvement in care: effects on patient outcomes.” Annals of Internal Medicine 102.4 (1985): 520–528.

- 2020 Value Assessment Framework: Proposed Changes. Boston: Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2019.

- Lakdawalla, D.N., et al. “Defining elements of value in health care—a health economics approach: an ISPOR Special Task Force report [3].” Value in Health 21.2 (2018): 131–139.

- Seidman, J., et al. “Measuring value based on what matters to patients: a new value assessment framework.” Health Affairs Blog (2017).

- Schnipper, L.E., et al. “Updating the American Society of Clinical Oncology value framework: revisions and reflections in response to comments received.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 34.24 (2016): 2925–2934.

- Bywall, K.S., et al. “Patient perspectives on the value of patient preference information in regulatory decision making: a qualitative study in Swedish patients with rheumatoid arthritis.” The Patient: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research 12.3 (2019): 297–305.

- Neuendorf, K.A. “Content analysis and thematic analysis.” Advanced Research Methods for Applied Psychology. Routledge, 2018: 211–223.

- Vaismoradi, M., H. Turunen, and T. Bondas. “Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study.” Nursing & Health Sciences 15.3 (2013): 398–405.

- Bywall, “Patient perspectives.”

- Neuendorf, “Content analysis.”

- Vaismoradi, “Content analysis.”