What’s Next for Value-Based Care in Cardiology?

Summary

The prevalence and cost of CVD make cardiology a strong candidate for value-based care. Various clinical and market trends present opportunities for continued uptake.Avalere invites you to download the accompanying white paper, which expands on this Insight.

Value-Based Cardiology Has Momentum, But Challenges Remain

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States overall and for individuals aged 65 and older, as well as the second leading cause of death for individuals aged 45 to 64. According to census projections, more than 30 million Medicare enrollees could require cardiovascular care by 2030. In the United States, direct costs of cardiovascular disease are projected to reach nearly $750 billion annually by 2035.

Over the past several years, value-based care (VBC) has become increasingly established in cardiology. Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Advanced (BPCI Advanced) is the only Medicare alternative payment model with specific cardiology episodes, which accounted for 25.3% of all participant episode selections in 2023. Other models, such as the Cardiac Rehabilitation Incentive Payment Model that CMS announced in 2016 but cancelled in 2017, have stalled.

Alongside nascent growth in government-led VBC models in cardiology, commercial payers or plan partners may have their own value-based incentives, such as the cardiology delegated-risk model offered by the specialty care management platform New Century Health (part of Evolent Health). In a 2022 survey designed and administered by Avalere, payers across lines of business ranked cardiology highest with respect to potential for VBC, suggesting both strong interest and an undersaturated baseline. Both clinical need and growing costs indicate a need to improve care, although the factors that shape this dual opportunity and challenge are complex.

Clinical and Market Dynamics Relevant to VBC

1. Most cardiologists are employed by hospitals and health systems, intensifying competition for physician labor and complicating pathways to value.

Cardiologists and other cardiovascular specialists offer important revenue streams for hospitals, and competition for physicians will increase as the country experiences a potential net loss of more than 500 cardiologists annually. In 2021, cardiac electrophysiologists averaged approximately $5.57 million in charges per provider, the second highest of any specialty or subspecialty. In that year, cardiac electrophysiology was the specialty or subspecialty with the lowest number of active physicians (2,632) and the highest number of people in the United States per active physician (124,076).

Figure 1: Cardiology Employment Statistics, 2019 and 2022

A 2022 report by Avalere and the Physicians Advocacy Institute found that the proportion of cardiologists who were employed (as opposed to practicing independently) increased from 73% in January 2019 to 85% in January 2022, the fifth highest rate of any medical specialty (Figure 1). In January 2022, 79% of employed cardiologists were employed by hospitals or health systems, entities whose consolidation of provider labor limits incentives to enter into value-based agreements. Simultaneously, corporate platforms or independent practices with less contracting leverage may be reluctant to transition from fee-for-service (FFS) revenue. For cardiology platforms looking to grow, this fragmentation makes the prospect of add-on acquisitions of physician groups both iterative and expensive, especially when competing against health systems.

2. The transition of key services to lower-acuity settings of care (SOCs) has been sluggish, and while significant white space remains, operational barriers persist.

Historically, the availability of multiple SOCs has been critical to the success of VBC. Given the procedure-intensive nature of much of the most expensive cardiovascular care, the transition to lower-acuity SOCs could reduce the cost of care. However, one source found that, between 2016 and 2022, only 3.6% of interventional cardiology procedures transitioned from hospitals to ASCs.

Device costs may represent a substantial proportion of the total cost of a procedure, potentially contributing to a continued preference for higher-paid sites of care to maximize margin. For example, the 2024 final rule for the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment Systems lists 501 device-intensive procedures for which the device represents at least 30% of the overall cost. For Level 3 Pacemaker and Similar Procedures, the device may account for 51.3—63.1% of the total cost in the hospital outpatient department (HOPD) but up to 65.9—75.8% of the total ASC facility payment, potentially making it difficult to maintain margin in the ASC.

Outside of FFS Medicare, we observe the potential for high variability in episode cost. One payer found up to 532% variation in the cost of a percutaneous coronary intervention episode within a single market. The variable and unpredictable patterns of expenditure for chronic cardiology patients make value-based arrangements challenging, especially for independent practices with more overhead and less leverage to negotiate device acquisition costs. Lastly, while the transition of cardiology procedures to outpatient settings is a tailwind for VBC, operational constraints – such as the 11 states with certificate of need laws that specifically restrict cardiac catheterization – help explain latency in SOC shifts.

3. Potential decreases to drug revenue may impact providers’ cost-benefit analysis around the relative attractiveness of FFS compared to VBC.

Many chronic cardiovascular conditions are treated with prescription drugs. In 2020, Medicare spent $7.7 billion on the 50 most utilized generic cardiology drugs. Five of the drugs selected for Medicare drug price negotiation in initial price applicability year 2026 (Eliquis, Jardiance, Xarelto, Farxiga, and Entresto) are cardiology drugs or are often prescribed by cardiologists. Avalere found that these drugs accounted for approximately $35.7 billion in Part D spending between June 2022 and May 2023, or about 30.5% of all Part D spending in fiscal year 2022.

Traditionally, value-based arrangements have focused on services (or Part A and B) spend while carving out drug (or Part D) spend. Thus, while a meaningful reduction in drug spend may not directly impact risk arrangements, it could impact their attractiveness. As the relative balance of traditional versus value-based arrangements evolves, a combination of education and investment will be critical to generating physician interest in VBC. Issues related to margin and profitability are compounded by the expansive scope of high-acuity cardiology services that patients are likely to need.

4. To date, the limited value-based initiatives in cardiology have not shown compelling clinical outcomes or strong financial returns.

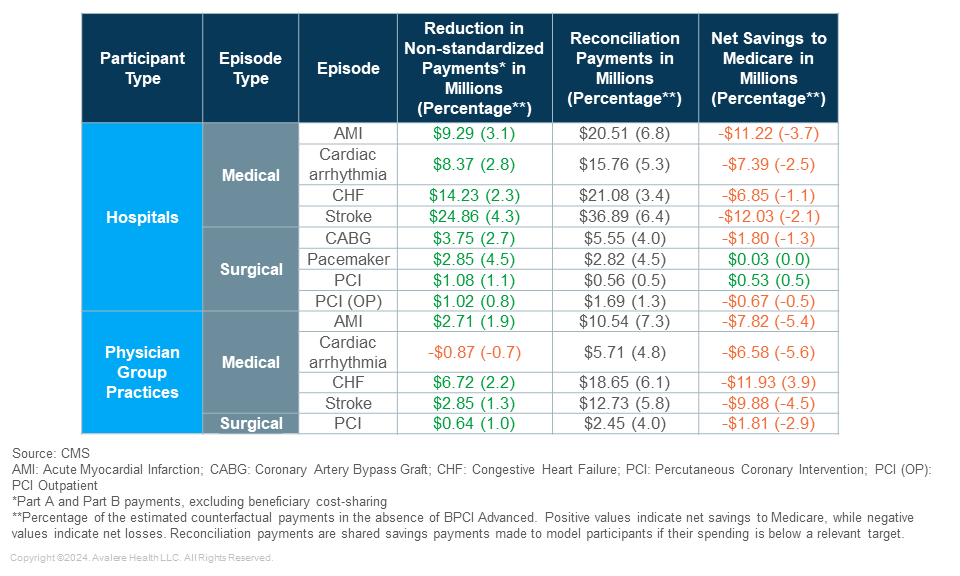

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ most recent report on BPCI Advanced covers Model Year 3 (2020) and indicates that BPCI Advanced resulted in net losses for Medicare. The program reduced non-standardized episode payments by roughly $514.1 million (about 3.8% of what payments would have been without the program), indicating gross savings. The program also paid $627.8 million in reconciliation payments (what participants earn when episode payments are below the target price), resulting in a net loss of $113.7 million to the Medicare program. Medical episodes represented a net loss of $200.5 million, but surgical episodes represented a net savings of $71.3 million. Together, these results demonstrate the challenges of value-based arrangements for medical cardiology while suggesting greater feasibility of such arrangements for surgical or interventional cardiology. Even if surgical costs are greater than medical costs on a per-episode basis, they may be more predictable.

Evaluation of the individual cohort data exemplifies the challenging nature of designing episodes of care that generate upside for both the participating provider and the payer. Table 1 shows that, across almost all cardiac medical and surgical episodes, both hospital and physician group practices generated savings (reductions in payments). After accounting for the reconciliation payments, however, the model generated net losses to Medicare across all but two hospital-based surgical episodes. Encouragingly, reductions in non-standardized payments suggest that cardiologists are able to generate savings by participating in VBC, but the relative magnitude of reconciliation payments suggests that providers and payers must pursue further alignment with respect to the expectation of savings.

Table 1: Net Medicare Savings, BPCI Advanced, Model Year 3 (January 1, 2020–December 31, 2020)

The evaluation report also shows mixed performance on patient-reported changes in functional status, activities of daily living, care experiences, and satisfaction with care. These results further exemplify the importance of alignment across stakeholders when developing an episode-based payment model, as well as the need to balance high-quality care with metrics that are achievable for participating providers.

Conclusion

As trends in disease burden, provider supply and demand, market fragmentation, site-of-care shifts, and drug and device costs have developed over the past several years, cardiology care has become increasingly expensive. Nonetheless, changing price dynamics and an aging population in need of cardiology services will accelerate the extent to which demand outpaces provider supply, creating compelling arguments for consolidation and value, though the macro environment for physician practice management (PPM) remains challenging.

To explore opportunities in cardiology or PPM, connect with us.